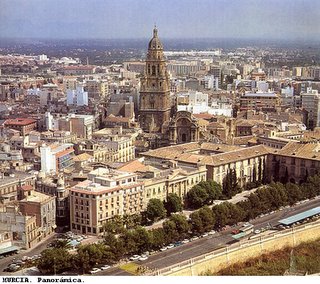

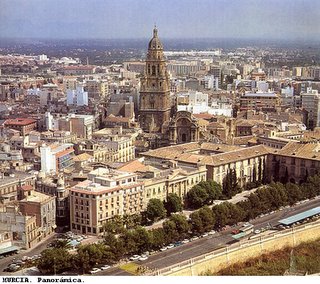

PERMANENT FORUM FOR EUROPEAN STUDIES MURCIA.

GENERAL COUNCIL OF THE JUDICIARY OF SPAIN

ONGOING TRAINING SERVICE

SEMINAR ON JUDICIAL COOPERATION IN MATTERS OF FAMILY LAW AND PARENTAL RESPONSIBILITY IN THE EUROPEAN UNION

On 28 to 30 September 2005, a Seminar was held in Murcia on judicial cooperation in matters of family law and parental responsibility in the European Union, with the participation of 42 European Union judges from Cyprus, Denmark, Estonia, Germany, Finland, Greece, Italy, Malta, Holland, Poland, Portugal, Spain and the United Kingdom with a view to analysing the current status of judicial cooperation in the field of family law and parental responsibility in the European Union, and examining ways for improving the application of Council Regulation (EC) n° 2.201/2003 of 27 November relating to competence, recognition and enforcement of judgments in matrimonial matters and parental responsibility, repealing Regulation (EC) n° 1347/2000, and which came into force on 1 March 2005.

One of the aims of the Seminar was to achieve maximum results and to draw up a guide to good practices which would condense the material compiled during the Seminar, and which would be accessible to all Member States, both in hard copy and also in digital form on the General Council of the Judiciary web site, using methods which have encouraged direct contact with judges from different countries working together in the application of common normative instruments from the perspective of different national legal systems. This has also has helped to establish mutual confidence between the judges. The agreement reached by the majority has produced a practical guide which complements that published by the European Judicial Network in civil and commercial matters, and which was based on the following:

CONCLUSIONS AND RECOMMENDATIONS

1.- Question. – The Regulation does not define a maximum age for children, relegating this question to the respective regulations in national laws. Although decisions on parental responsibility generally concern children under 18, these individuals may be emancipated, pursuant to national legislations, particularly if they marry. The decisions issued in respect of these persons are not considered, in principle, to be a matter of “parental responsibility” and therefore, they do not come within the scope of the Regulation. In Spain there is also the possibility of applying the Regulation to children of legal age in cases of incapacity, such as in Art. 171 of the Spanish Civil code. It should also be recalled that in the case of Spain, the majority is reached on the person's eighteenth birthday, pursuant to Art. 315 of the Civil Code, however, emancipation also occurs if the child marries (which gives rise to emancipation under law) through its grant by guardians (in which case the child must be over 16 and must give consent) and may be granted to children over 16 through legal bodies.

Recommendation.- The Courts will resolve each specific case in the application of Regulation 2.201/2003, with respect to age, pursuant to their national legislation, and shall do so due to the differences in the national legislation of each country in matters such as incapacity of persons of legal age and the possibilities of children acting as emancipated in specific cases, and they shall do so, if appropriate, until there is jurisprudence from the Court of Justice of the European Communities.

2.- Question.- The possibility of treating matrimonial issues and those of parental responsibility, either jointly or through various jurisdictional bodies may pose some practical problems. In Spain it has been noted that the system of sharing issues between various jurisdictional bodies could hypothetically give rise to contradictory judgments in the various sectors of family matters, on one hand, and child protection on the other. It might be appropriate to implement regulations for this division of issues which would channel all the matters raised in relation to the same family conflict, so that they could all be heard by the same Court.

Recommendation.- It was stressed that there was a need for every country to adapt its procedural and organisational regulations so that the same Court or authority would have authority to resolve all the issues within the scope of application of Regulation 2.201/2003, and the other international Conventions in existence, in addition to Community Regulations directly relating to it, as occurs with Regulation 44/2001 and the Hague Conventions of 25 October 1980 and 19 October 1996.

3.- Question.- In respect of the matters raised in Art. 1.2 of Regulation 2.201/2003, it was debated whether this list of issues should be considered exhaustive and closed, or whether it is simply provides examples.

Recommendation.- In every specific case it is the competent authority of each country which will determine whether the issue in question in the sector of parental responsibility is within the scope of application of Regulation 2.201/2003, bearing in mind that the list of issues contained in art. 1.2 serves purely as an example or guide. The concept of parental responsibility should always operate on the basis of the superior interests of the child. As possible good practice, it was considered appropriate to ensure that in decisions awarding custody to one of the parties in a procedures involving matrimonial crisis, it would always be expressly stated whether or not custody implied the possibility of deciding unilaterally on any changes of residence to another country.

4.- Question.- The obligations of food and questions relating to parental responsibility are governed by different Regulations. Issues of food obligations are proper to Regulation 44/2001 and parental responsibility is an issue proper to Regulation 2.201/2003. The possibility was discussed of dealing with both matters, if appropriate, in the same procedure.

Recommendation.- When appropriate, it would be advisable to process claims or applications relating to food obligations and parental responsibility together, despite the fact that they are governed by different Regulations, without prejudice to providing an individualised response to each of the petitions. The resulting judgment would be recognised and executed in accordance with diverse regulations. An overall solution is required for the various claims in the same procedure.

5.- Question.- With respect to the term “decision” in Art. 2 of Regulation 2.201/2003, it was discussed whether for the purposes of recognition and enforcement; it included solely positive decisions, or also overruling judgments or dismissals.

Recommendation.- The term «decision» refers solely to positive decisions which lead to a divorce, a legal separation or annulment of marriage. With regard to decisions on parental responsibility included in the scope of the Regulation, and subject to the rules of competence thereof, some positive decisions may have negative effects with respect to parental responsibility for a person other than the individual in whose favour the decision was issued. These should also be included.

6.- Question.- There is no regulation on the cases of dual nationality for the purpose of criteria of competence.

Recommendation.- If there is a problem, the jurisdictional bodies of each State shall apply their internal rules within the framework of the general regulations in this respect.

7.- Question.- In respect of Art. 9, there was discussion on the competence of the State where the child newly resides to set an access and visiting regime, and the moment from when that competence would apply to this State.

Recommendation.- It was considered that if the parties agree, the new State of residence of the child shall have competence in regulating the visiting system affecting the child, right from the start. If there is no agreement, the child's new state of residence could take provisional measures (art. 20). Without prejudice to the foregoing, the parent remaining in the State of previous residence may apply for an appropriate change in the visiting regime to the Court which granted it, during the three months following the change of residence. The three month term referred to in Art. 9, should be counted from the date on which the child physically leaves the Member State of origin.

8.- Question. With respect to child abduction, the question was raised as to whether judges and authorities dealing with these issues should receive special training, due to the particular complexity and the nature of the problems arising through the various international instruments.

Recommendation- The participants were unanimous in considering that specialised judges and authorities are required, both in first and second instance, as indeed the need to concentrate knowledge of these matters in a limited number of Courts or centres. In those States in which no specialisation exists, intensive training should be provided to all judges and authorities acting in these matters. Despite the fact that the organisation of the authorities and Courts lies beyond the scope of Regulation 2.201/2003, for those Member States which, when hearing matters relating to the Hague Convention of 25 October 1980 have concentrated competence in a limited number of Courts or judges, the experience has been positive, reflected in an increase in quantity and effectiveness, unanimously recognised. A good practice in application of the regulation should involve Member States in a commitment to improve the human and material resources of Central Authorities. It was recommended that the European Judicial Network in civil and commercial matters should include among its members specialists in family law, parental responsibility and international abduction of minors.

9.- Question.- There was discussion on whether a different inter- and extra- community regulation would generate complexity or a defective working of the system.

Recommendation.- To date, no dysfunctions have been noted in the simultaneous application of both regulations.

10.- Question.- Whereas the Hague Convention of 2 October 1980 is only applicable to children under 16, there is no such express age limit in Regulation 2.201/2003. There was discussion as to whether the Regulation was applicable to children under 18 and over 16 in the area of international child abduction.

Recommendation.- It is not possible to apply the Regulation 2.201/2003 to children aged between 16 and 18 because the Regulation, where it does not exactly specify, maintains the provisions of the Convention of 25 October 1980, which is what really differentiates the applicable age.

11.- Question.- Having presented the application for return, pursuant to Regulation 2.201/2003, with respect to an abduction occurring prior to the date of its effective application, the question of its admissibility was raised.

Recommendation.- Art. 64.1 of the Regulation 2.201/2003 should not prevent application of the new Regulation to return applications presented after 1 March 2005, despite the fact that they refer to abductions from an earlier date.

12.- Question.- The question was discussed of how the exceptional possibility of avoiding a child’s hearing should be interpreted in article 11. 2 of Regulation 2.201/2003.

Recommendation.- It was proposed to interpret in a very restrictive manner the exception concerning the fact that a child cannot be heard if it is not considered appropriate, due to its age or degree of maturity, or other personal circumstances which have an effect on its maturity.

13.- Question.- There was discussion on how to combine the term of six weeks determined in article 11.3 of Regulation 2.201/2003, with the need to hold a hearing for the child.

Recommendation.- By making use of the resources of teleconference and video conference, within the framework of Regulation 1.206/2001, it is possible to hear the child within a term of six weeks. This six week term, in order to issue a decision, should be observed in all procedures unless there are very exceptional circumstances.

14.- Question.- With respect to the importance which the Regulation 2.201/2003 accords to the child’s hearing, it was attempted to determine whether there is any regulatory imposition which would ensure that the hearing takes place, despite the fact that such provision may not exist in the national legislation of each country.

Recommendation.- It was considered that Regulation 2.201/2003, in the matters of hearing children totally respects the international regulations of each State applicable in this matter. Throughout the seminar the appropriateness of hearing children was widely debated, paying all due respect to the forms and means of carrying out such hearings, pursuant to the different national laws, since it is of paramount importance that the child is able freely express its opinions through an examination carried out in a manner appropriate to its age and degree of maturity.

15.- Question.- with regard to Art. 11.3 of Regulation 2.201/2003, it was questioned whether a judgment issued should be enforced within a term of six weeks.

Recommendation.- Section 3 of article 11 of Regulation 2.201/2003, does not specify that judgments issued within a term of six weeks, should be enforced within the same term. It was considered desirable that the national regulations of each country would make them enforceable, without prejudice to resolving every specific case, since some opinions were expressed in favour of waiting to have the results of the decision of the second instance.

16.- Question.- With respect to Art. 11.4 of Regulation 2.201/2003, it is obvious that it extends the obligation to order the return of the child in cases where it may be exposed to such dangers, but it has been shown however, that the authorities in the Member State of origin have adopted or at least are prepared to do so, suitable measures for ensuring protection of the child after its return. How this would have to be demonstrated was discussed, as well as which jurisdictional body would decide in the matter.

Recommendation.- Although, when the Court of origin has issued a judgment declaring that such measures should be taken, it should abide by that decision, it was considered that there should be sufficient demonstration that the appropriate specific measures have been taken to protect the child in a particular case. It was not enough that a generic provision exists to ensure that adequate protection measures would be taken. The demonstration of the adoption of specific measures should be made in each case on the basis of the facts of the case.

17.- Question.- With regard to the provisions of art. 11.5 of Regulation 2.201/2003, it was discussed whether the possibility of hearing a person who had applied for return of a child may or may not presuppose an element requiring an in-depth analysis of the dispute beyond the mere decision of return or non return..

Recommendation.- It was considered that this would create a conflict of interests differing from those of the best interest of the child, and such a hearing would be an important condition for the possibility of refusing the return and for issuing the certification pursuant to art. 42 of Regulation 2.201/2003,

18.- Question.- A detailed analysis of art. 11.6 of Regulation 2.201/2003 raised several technical difficulties. It was discussed how these could be resolved in a practical manner, and what the implications were of the need to serve a copy of the judgment of non return and the pertinent documents, in particular the record of the hearing, pursuant to the provisions of national legislation.

Recommendation.- It was stressed that there was a need to ensure that the information sent to this effect should be as extensive as possible, and that the judge or body issuing the judgment should decide which documents were pertinent, seeking pragmatic solutions in the matter of any possible translations, which the rule itself does not address. Agreements could be reached on what should be sent if there were considerable differences to the national procedural rules. It should be remembered that on this issue the European Judicial Network in civil and commercial matters and the Central Authorities can be of considerable assistance, since in the framework of art. 55 c) of Regulation 2.201/2003, they include among their main functions that of facilitating communications between Courts, in particular for the application of sections 6 and 7 of articles 11 and 15.

19.- Question.- With respect to art. 11.6 of Regulation 2.201/2003, the question was discussed of which Court should transmit the decision of non-return.

Recommendation.- The judgment shall be conveyed to the competent Court or the central authority of the Member State in which the child habitually resided prior to its illegal removal or retention, that is, the Court authorised to hear the main case which is the question of custody. On this point the suggestions of the European Judicial Network in this matter are assumed in the practical guide where it states that if a Court of the Member State had previously issued a decision in respect of the child in question, the document will in principle be transmitted to that Court. If no judgment has been issued, the information will be sent to the competent Court, pursuant to legislation of the Member State which, in most cases, will be where the child habitually resided prior to its abduction. The European Judicial Atlas in civil matters may prove a useful tool in finding the competent jurisdictional body in another Member State (Judicial Atlas). The central authorities designated pursuant to the Regulation may also help judges to find the competent body in each Member State.

20.- Question.- There was debate over Art. 11.7 of Regulation 2.201/2003, and the fact that it does not include any temporary limit for the competent Court to examine the question of the child’s custody. The issue of whether or not that precept limits the competence of the State to decide on custody was discussed.

Recommendation.- It was considered that the Court of origin will examine the question of custody if at least one of the parties submits allegations to this effect. Although the Regulation does not impose any term in this respect, the aim should be to adopt a decision as soon as possible. The meaning of Art. 11.7 of Regulation 2.201/2003 can be clarified to ensure its correct implementation in the sense that this rule does not restrict the competence of the State of origin to decide on the child’s custody alone. In these cases, the competent body resolves the main question pursuant to national law, and without the imposition of short term periods or urgent measures or preferential procedures of any kind. It was pointed out that if the final decision issued were to be delayed in time, it would almost certainly lose all the immediacy which the final decision demands in these cases in the interests of safeguarding the prevailing interests of children.

21.- Question.- Regarding the debate on conditions referred to in Art. 12.3 a) of Regulation 2.201/2003, the question was raised of whether or not such conditions should be considered exclusive.

Recommendation.- It was considered that these conditions should not be considered exclusive and that there could be different conditions, and it would be possible to base the close links a child had with a Member State on other factual criteria. The fact that a child has a close link with a Member State is not limited to situations in which the child habitually resides in the territory of a Member State, but also applies when it has its habitual residence in the territory of a third State which is not a party to the Hague Convention of 1996.

22.- Question.- There was debate on the lack of a specific fixed term which should be established pursuant to art. 15.4 of Regulation 2.201/2003.

Recommendation.- With respect to Art. 15.4, it was emphasised hat although the Regulation doe not set a maximum term, it is understood that the term set in each case should be sufficiently short to ensure that the return does not give rise to unnecessary delays, to the detriment of the child and the parties. A maximum term of 3 months was suggested as appropriate, with a provision for extending this period.

23.- Question.- The lack of translating mechanisms was discussed as these were not addressed in art. 15 of Regulation 2.201/2003, and also which would be the most effective means of communication between he issuing and receiving bodies

Recommendation.- With respect to Art. 15.4 of Regulation 2.201/2003, it was stressed that it is the Central Authorities which have to facilitate communication between Courts, although that does not rule out direct contact between them, via telephone, fax or e-mail. Practical solutions should avoid any problems which could arise through a lack of translation, with the central authorities collaborating in the task of translating, even if only informally, thus easing the procedural process.

24.- Question- Regarding the application of Art. 18 of Regulation 2.201/2003, it was debated whether or not it contains an obligation of suspension and the manner in which this might be assessed.

Recommendation.- With respect to this fact, it is considered that there is an obligation to suspend on the part of the Court, not a mere power to do so, and that the rights to defence of the respondent shall be taken into account by the Court, both in respect of « the sufficient time for the defendant to prepare his defence » and in respect of the fact that “all necessary steps have been taken to this end ».

25.- Question.- Following analysis of Art. 19 of Regulation 2.201/2003, a positive assessment was made of the way in which it addresses the regulation of litispendence and dependent actions, having evaluated the different comparative legal systems in respect of this question.

Recommendation.- It was deemed that linguistic precision should be assessed due to the fact that the English expression “the same cause of action”, is translated in Spanish as el mismo objeto y la misma causa, (the same action and the same cause) something which is significant for the interpreter as the concept and requirements of lis pendens are not the same in all countries. It should be remembered that this idea is stricter in some States than in others (such as France, Spain, Italy or Portugal) in that the same object, the same cause and the same parties are involved, as opposed to those in which the idea of lis pendens is broader and refers only to the same object and the same parties.

26.- Question.- The vest way of implementing Art. 20 of the Regulation was discussed in respect of the use of cautionary measures.

With respect to cautionary measures, and as good practice, it could be said that in a case where a Court issues cautionary measures in respect of a family conflict which is being heard by the Court of another Member State, a copy of the decision should be served immediately, by the most rapid means, to the Court, requesting acknowledgement of receipt. In the decision to issue cautionary measures, a brief period should be established so that the interested party which had obtained the decision may approach the competent Court, which has already heard the main proceedings, to apply to that Court to proceed, immediately bringing an end to the cautionary measure agreed prior to expiry of its temporary duration, or prior to enforcement of the final decision issued by the competent Court.

27.- Question.- The important question was raised of the interpretation of Art. 21.2. Regulation 2.201/2003, in respect of whether or not recognition of the records requires prior examination of the agreement on causes for refusal, before updating the information in the civil registers

Recommendation.- Regarding this question, the majority considered that this rule regulates automatic recognition of records, something which prevents an analysis of whether or not the causes of refusal or recognition concur. It was considered it would be sufficient to carry out a formal check to ensure that the documentation presented is that required pursuant to the Regulation and that which pertains to the decision, with no admission of appeal.

28.- Question.- There was an analysis of the grey areas which interpretation of the concept of the interested party may raise, for example in Art. 21.3, and other similar precepts, as in questions affecting parental responsibility, the question of legitimisation of either of the parties in the original proceedings may raise questions of interpretation when the legitimisation of relatives depends on the national legislation of each country. Nevertheless, Art. 23. d of the Regulation prevents recognition of a decision on parental responsibility on application of any person alleging that the judgement infringes his or her parental responsibility, if it was issued without such person having been given an opportunity to be heard. This may considerably extend the concept of legitimisation.

Recommendation.- On this question the majority considered that given the lack of definition of the concept of interested party in Art. 2 of Regulation 2.201/2003, a broad concept should be adopted for the purpose of the provisions of this Regulation and that the superior interest of the child should always be taken into account. In issues of access rights, for example, Regulation 2.201/2003 applies to any access rights, irrespective of who is the beneficiary thereof. According to national law, access rights may be attributed to the parent with whom the child does not reside, or to other family members, such as grandparents or third persons. The new rules on recognition and enforcement apply only to judgments that grant access rights. Conversely, decisions that refuse a request for access rights are governed by the general rules on recognition

29.- Question.- The implications of incidental recognition permitted pursuant to Art. 21.4. of Regulation 2.201/2003 were examined.

Recommendation.- It was considered that it was for reasons of simplicity that it was advised that the Courts hearing the main case should have competence to hear recognition of decisions which are incidental. In this way if the foreign judgment is alleged again in further proceedings, the Court which has to hear this second case will not be bound by the previous judgment issued in an incidental manner in the earlier case.

30.- Question.- The question of the “Law of the Member State” was examined as contained in Art. 25 del Regulation 2.201/2003.

Recommendation.- Regarding Art. 25, it was concluded that the expression “law of the Member State” refers not only to the national law of each State but that it includes both material national regulations of each state, as well as the rules of private international law. It is a question of ensuring that the differences between material systems of the Member States do not end in non-recognition.

31.- Question.- With regard to Art. 31 of Regulation 2.201/2003, the possibility was examined of specifying a concrete term and also the possibility of acting prior to issuing a decision .

Recommendation.- In terms of Art. 31 it was concluded that there was a need to issue a judgment as rapidly as possibly without this preventing intermediate actions such as summons to complete insufficient documentation or transfers to the Public Prosecutor for informative purposes if appropriate.

32.- Question.- Various aspects of Art. 32 of Regulation 2.201/2003 were discussed.

Recommendation.- The need was emphasised of referral to the Member State to which application was made, in respect of the means of notification. Regarding notification of the applicant, the question was raised of the need to also notify the conflicting party, and not only when the decision accepted the application, in the event, for example, that the application was for non-recognition of a decision, but irrespective of whether the decision was accepted or refused.

33.- Question.- With reference to arts. 47 and 40 to 45 of Regulation 2.201/2003, the implications of rules of national state regulations, for example Art. 158 of the Spanish Civil Code in that they permit the adoption of urgent measures which could negate regulatory provisions for recognition and enforcement and abolition of the exequatur in area of access rights and return of children. It was pointed out for example that Art. 158 of the Spanish Civil Code establishes that: “..The Judge, either officially or on application of the child itself, any relative or the Public prosecutor, shall issue: 1º.- The appropriate measures for ensuring provision of food and the provisions for the future needs of the child, should this duty fail to be fulfilled by its parents. 2º.- The appropriate provisions for avoidance of harmful disruption in the event of any change in guardianship. 3º.- The necessary measures to avoid the abduction of underage children by either of their parents or by third persons and, specifically, the following: a) Prohibition on leaving national territory, except in the event of prior judicial authorisation. B) Prohibition on issue of a passport to the child or withdrawal thereof if it has already been issued. C) The submittal to judicial authorisation of any proposed change of address of the child. 4º.- In general, any other provisions considered appropriate for distancing the child from danger or to avoid harm. All these measures may be taken in any civil or penal proceedings or either in a voluntary Court procedure”.

Recommendation.- Having considered the possible role of Art. 158 of the Civil Code in the context of compliance with an enforcement order pursuant to Art. 40 of Regulation 2.201/2003, it was agreed that in these cases the Community Regulation prevails over national rules and totally prohibits in such cases the possible temptation to use Art. 158 of the Civil Code in a specific case, despite the provision of Art. 47.1 of the Regulation which proposes national legislation for the purpose of enforcement, so that in fact, by abolishing the exequatur, national law is substantially modified in an effective way. A Spanish judge may make use of Art. 158 of the Civil Code in the enforcement of a national case but not in a community dispute, where use of Art. 158 of the Civil Code will not be possible. Rules similar to Art. 158 of the Spanish Civil Code were indicated by several seminar participants in respect of their own countries’ legislations.

34.- Question.- Possible good practices within the framework of Art. 41, Regulation 2.201/2003 were suggested which would ensure its successful application.

Recommendation.- On possible good practices within the framework of Art. 41, it was agreed to suggest to judges that issue of certification should be carried out as rapidly as possible, without delay, and that if there was a real or potential possibility that the access rights could have a cross-border character, it would be advisable to issue the certificate at the same time as the judgment. This could, for instance, be the case where the holders of parental responsibility are of different nationalities or where the Court in question is situated close to the border of another Member State.

35.- Question.- Possible suggestions were analysed as a practical guide to the best means of applying Art. 42 of Regulation 2.201/2003

Recommendation.- In respect of best practices within the framework of Art. 42, it was agreed to propose to judges the need to broadly motivate decisions affecting the return of children. The need was emphasised for encouraging direct contact, by means of central authorities, between Courts involved in the decision of whether or not to return the child. Only in this way would it be possible to ensure that the Court of origin, when issuing its decision, could take into account the reasons and the evidence on which to base the judgment of non return issued in virtue of Art. 13 of the Hague Convention of 25 October 1980, and as required pursuant to Art. 42.2.c) of Regulation 2.201/2003.

36.- Question.- The issue was discussed of whether Art. 46 of Regulation 2.201/2003 place specific public documents and agreements between parties on the same plane as Court decisions.

Recommendation.- It was considered that public documents will include documents issued by notaries and this was assumed in respect of agreements between parties, provided that they are enforceable in the Member State of origin, that they are assimilated in the concept of legal decision with the obvious purpose of encouraging the conclusion of agreement between parties, irrespective of whether it is a case of a private agreement between the parties or an agreement concluded before an authority. In the case of Spain, the validity of Art. 770, 7ª of the Law on Civil Procedure was recalled, following the reform pursuant to the Law 15/2005, of 8 July, which now permits parties in a matrimonial case, by mutual agreement, to request suspension of the procedure pursuant to the terms of Art. 19.4 d of the Law on Civil Procedure, and to submit to mediation. In Spain it should be remembered that the Organic Law. 1/2004, of 28 December on Measures for integral protection against gender violence in art 44 thereof, introduces an Art. 87 ter to the Organic Law of the Judiciary which prohibits access to mediation in all cases of violence against women heard by the Court. In the seminar sessions it was concluded that mediation is extremely useful in cases of international child abduction.

37.- Question.- With respect to Central Authorities, the possibility of improving their operational capacity was discussed.

Recommendation.- Assuming that perhaps the expressions used in arts. 53 to 58 of the Regulation 2.201/2003, might be seen as somewhat ambiguous, participants drew attention to the excessive work load which some Central Authorities had to bear, and all acknowledged their vital role, and it was the wish of all participants that they were provided with sufficient financial and human resources needed to carry out their important work .

38.- Question.- Various practical cases were analysed in respect of the transitory provisions of the Regulation.

Recommendation - It was agreed to consider that when Art. 64 of the Regulation 2.201/2003, refers to the application of Chapter III for recognition and execution of decisions, that it implies application of measures to abolish the exequatur pursuant to arts. 40 to 45 of the Regulation, even in the case of judgments issued prior to the effective date of application of the Regulation, according to the conditions imposed by the literal stipulation of the rule in question.

Murcia, September 2005.

|

Sem comentários:

Enviar um comentário